The Fertility Crisis and the Postmodern Marriage Pattern in Germany

First came low marital fertility, then came extremely late marriage

Last time we explored the emergence of the MWEMP, or the Modern Western European Marriage Pattern, and how it contrasts with the HMP, the Historical Marriage Pattern. Under the HMP, women are married in the teens, usually to men in their twenties. In the MWEMP, women are married in the twenties, usually to men also in their twenties. We also defined the PMP, the Postmodern Marriage Pattern, which is what we currently have, and which is characterized by women marrying in their thirties.

I hypothesized in the last article that the MWEMP and the HMP are both caused by decreased infant and youth mortality, leading to a higher number of mutations persisting in the gene pool, which negatively affect breeding behavior, causing mutants to delay their own marriage, which in turn disrupts the marriage market, pushing the population mean higher than what mutations alone would do. Davide Piffer has, since then, provided additional evidence for this position, showing that countries with higher life expectancies have lower fertility on average. Specifically, within a country, cohorts who grew up under higher average life expectancies and higher GDPs went on to have lower complete fertility.

It seems implausible that this is due to some kind of learning mechanism. Shouldn’t normal learning agents tend to reproduce more when times are good? When your nation is wealthy, it’s time to breed a lot — you have more money for kids. When kids survive longer, they’re easier to raise to adulthood, so that’s another reason to have more. In marginalist microecon terms, the intrinsic desire for a marginal child stays the same (demand), but the average relative cost in terms of utility falls, meaning the psychological “price” goes down, so people should have more children. It’s likely then that the intrinsic desire for children actually goes down as they get easier to make. I doubt people could learn this response, so it must be a genetic process, either the accumulation of genetic damage due to a fall in filtering by selection (life is less deadly, longer lifespans), or an epigenetic mechanism which was selected for by group selection in times where wealth accumulation was more volatile and cyclical, and booms led to awful busts, potentially driving groups that did not respond to wealth with reduced fertility to extinction.

EO Wilson discusses this latter idea at length in his book Sociobiology.1 He calls it density dependence. There is a 2008 paper applying it to humans, and it finds that wealth is a strong predictor of TFR. It says:

Until recently in most countries, the main cause of reduced population growth in humans has been premature death. The models developed here describe a population with density-dependent growth similar to those widely used in population biology to capture the effects of limited resources on the growth of natural populations. However the present model represents a kinder, gentler form of density dependence, associated with socioeconomic development rather than famine or pestilence.

It seems there is some mechanism whereby humans respond to better conditions by reducing fertility, instead of always maximizing reproduction. But how does it work exactly? My top hypothesis for the ultimate cause is mutational load. In this article we’ll look at the proximate workings more closely.

These workings can be decomposed into separate parts:

Decline of marriage

Changes in marital fertility

Due to marriage delaying

Factors other than marriage age delaying

Changes in nonmarital fertility

To tackle this, we’ll want to find out the fertility of married and unmarried people by year, the average age of marriage by year, and the rate of marriage by year.

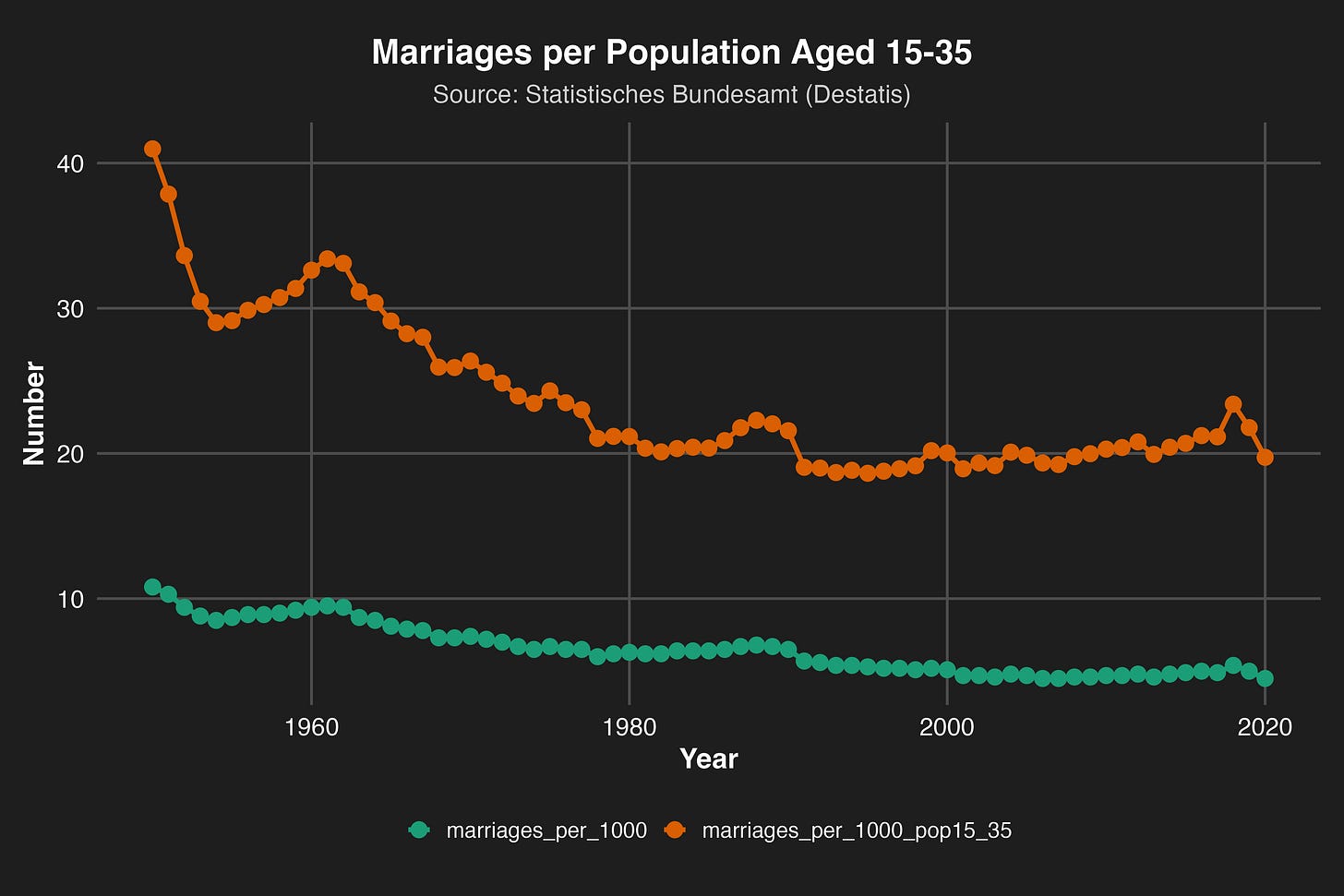

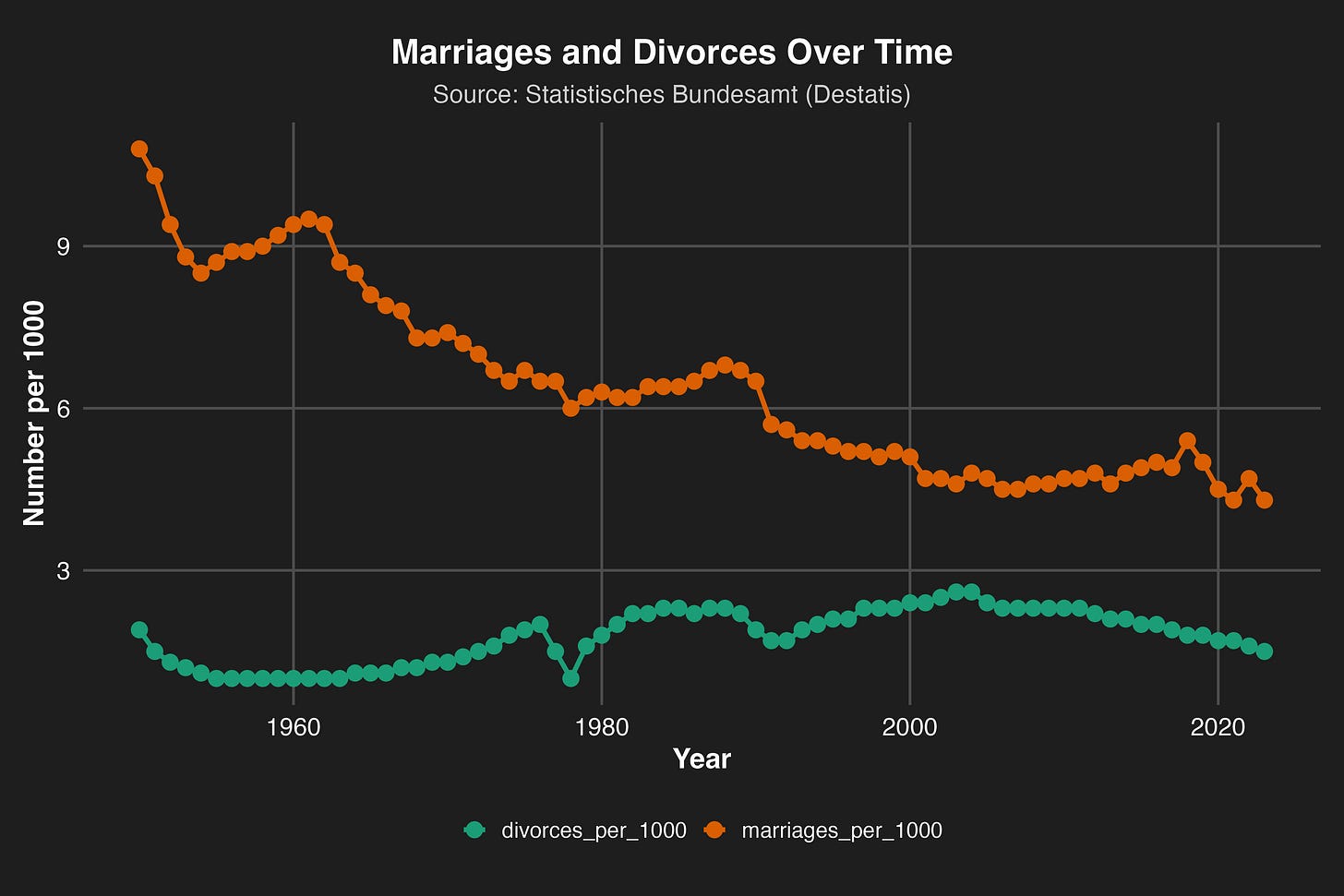

We’ll use Germany as our model nation. As you can see, the divorce rate is mostly stable, but the marriage rate is falling approximately linearly.

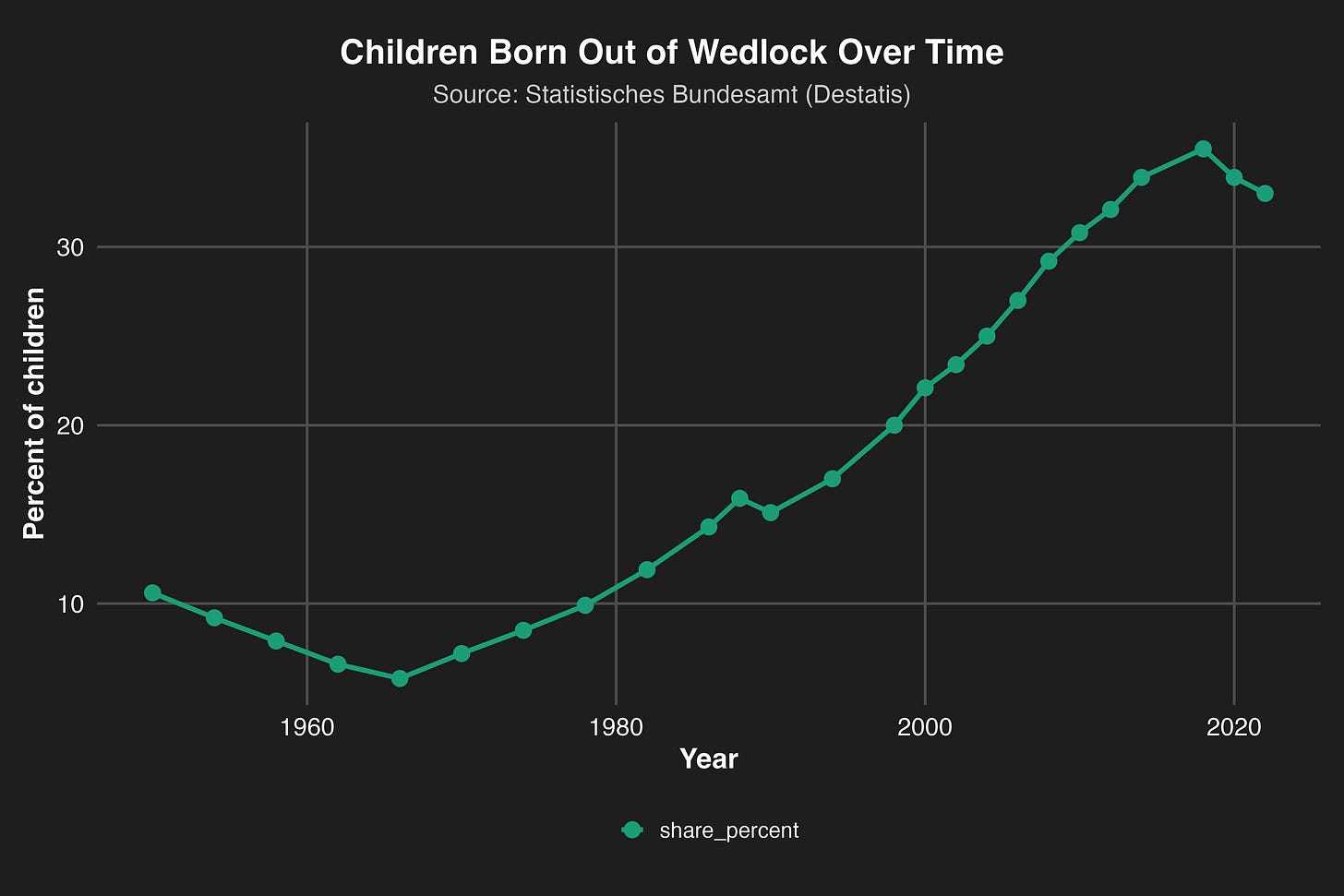

In tandem, the percent of children born out of wedlock has gone up.

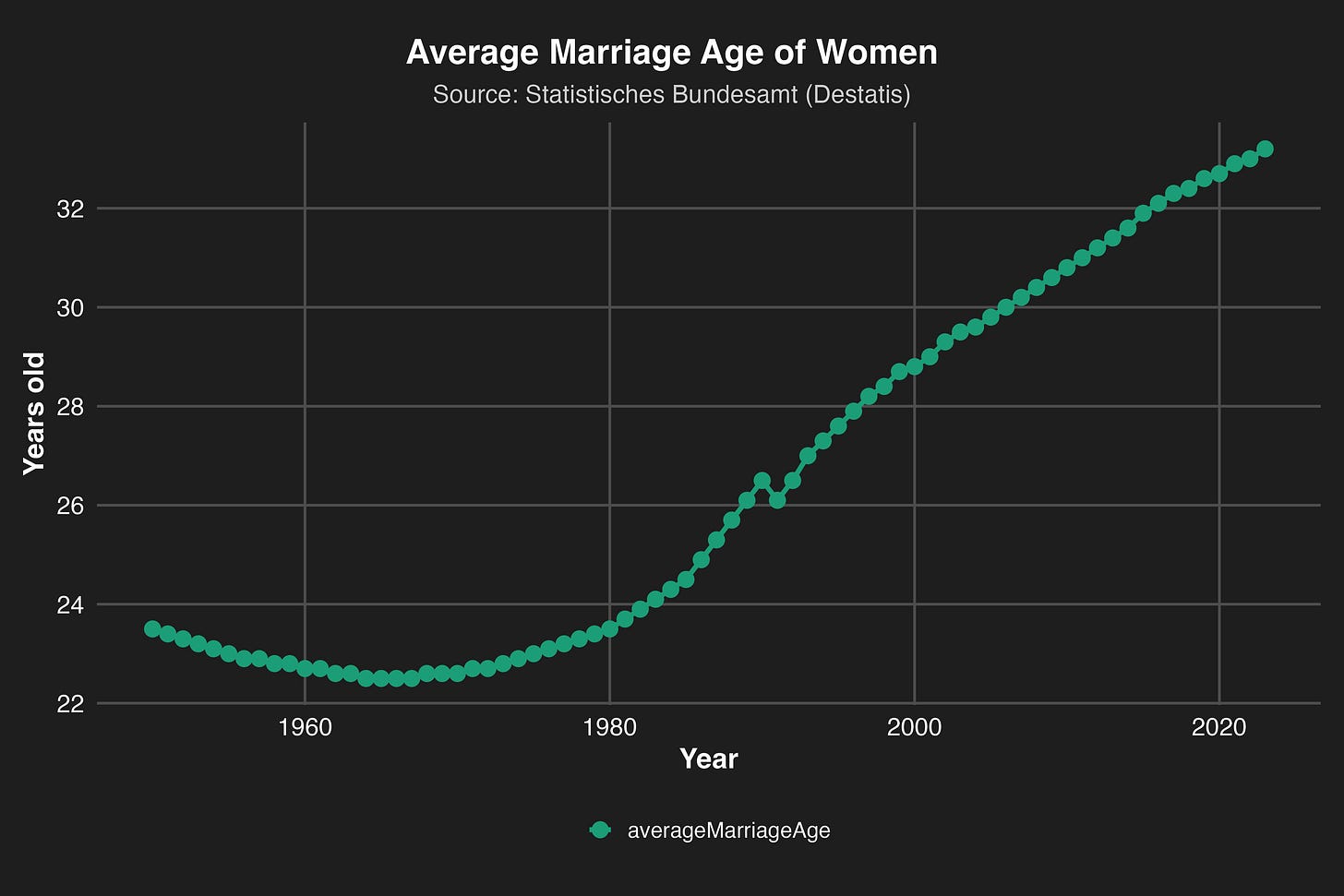

And the children born out of wedlock curve looks almost the exact same as the average age of female marriage.

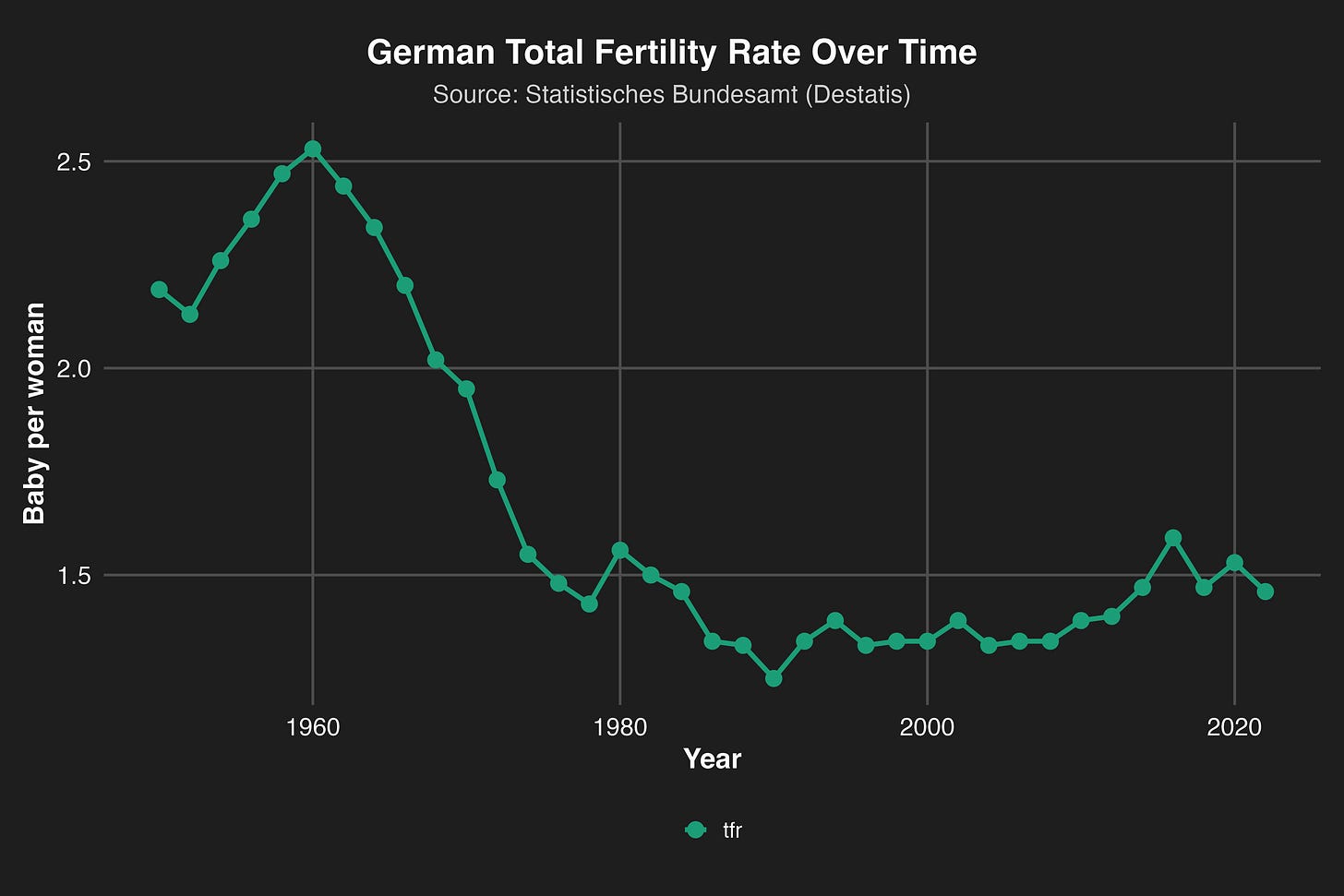

Finally we have the TFR.

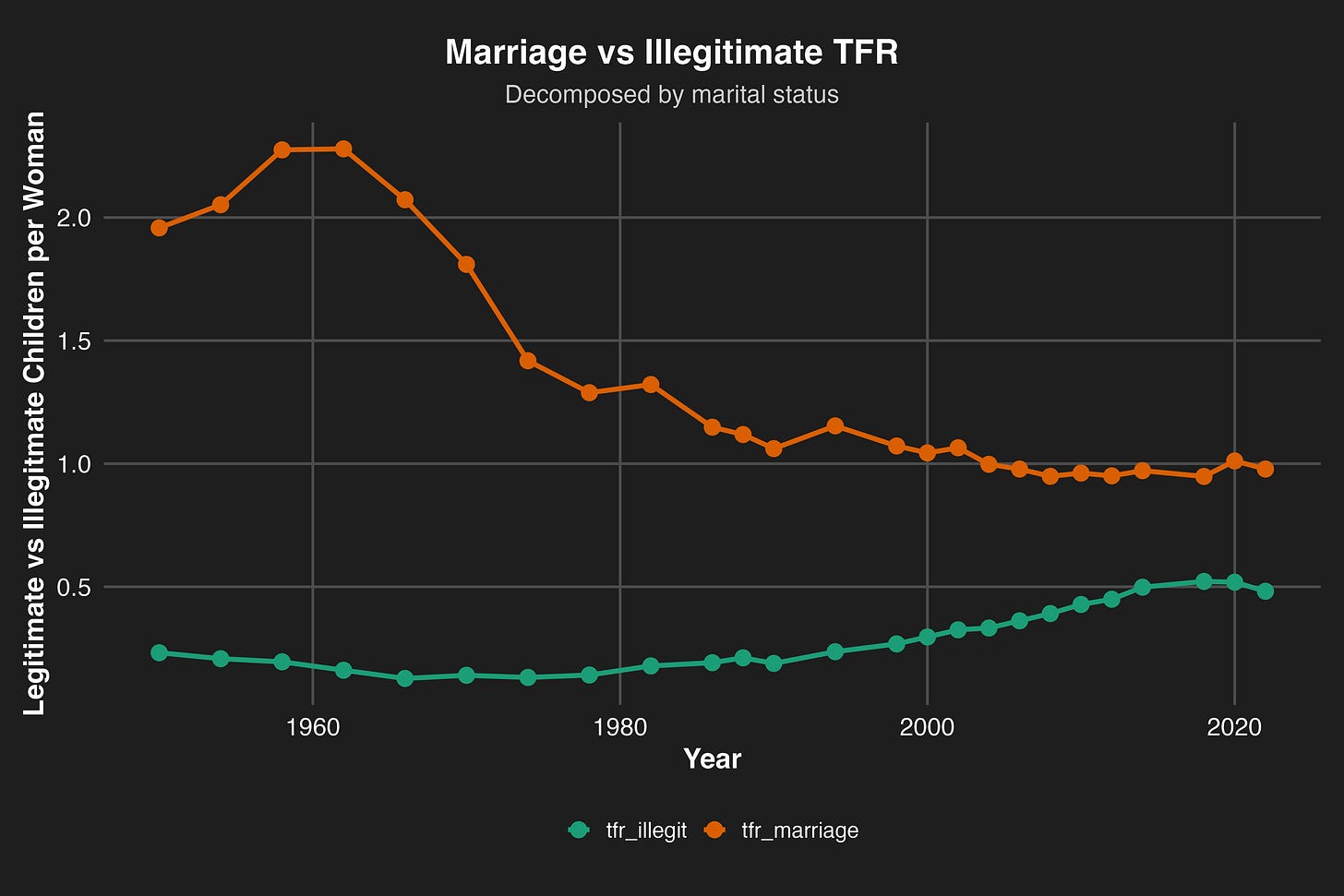

Here’s TFR decomposed by marital status. I think I see something nonlinear happening here which is this: after about the age of 28, delayed marriage does not decrease the TFR of married couples. I suspect this is because they want 1 kid, and by the age of 30, accidental pregnancy is very rare, because of the low fecundity of the woman as well as the man, who will also tend to be over 30. If they marry at, say, 33, they try really hard to have their 1 kid, often attempting insemination for a whole year, which would sound absurd to married 20 year olds who have to worry about accidental pregnancy from Cowper’s fluid (NSFW warning).

Then, as the age of marriage decreases from 28, TFR increases quadratically. This is likely due to a mixture of increasing risk of accidental pregnancy, as well as increasing odds that a couple decides they want a marginal child while still young enough to have one.

Is this story accurate? Causal inference suggests so:

The statistical analysis based on the 2009 Nationwide Fertility Level and Family Health and Welfare Survey shows that an increase of one year in age at first marriage reduces the likelihood of any childbirth (extensive margin) by about 8 percentage points (10%) and total childbirths (intensive margin) by 0.1 children (6.3%).

From 1970 to 2020, the average age of German marriage went from about 22.5 to 32.5, and the marital TFR fell from 2 to 1.

But on the other hand, we get a curve that looks a lot like the TFR if we just look numbers of marriages rates weighted by the amount of marriage aged people in the country.

This could suggest that a roughly 9 year increase in the average age of marriage from 1980 to 2020 led to only a .25 TFR reduction among married couples, and this was made up for completely by births out of wedlock.

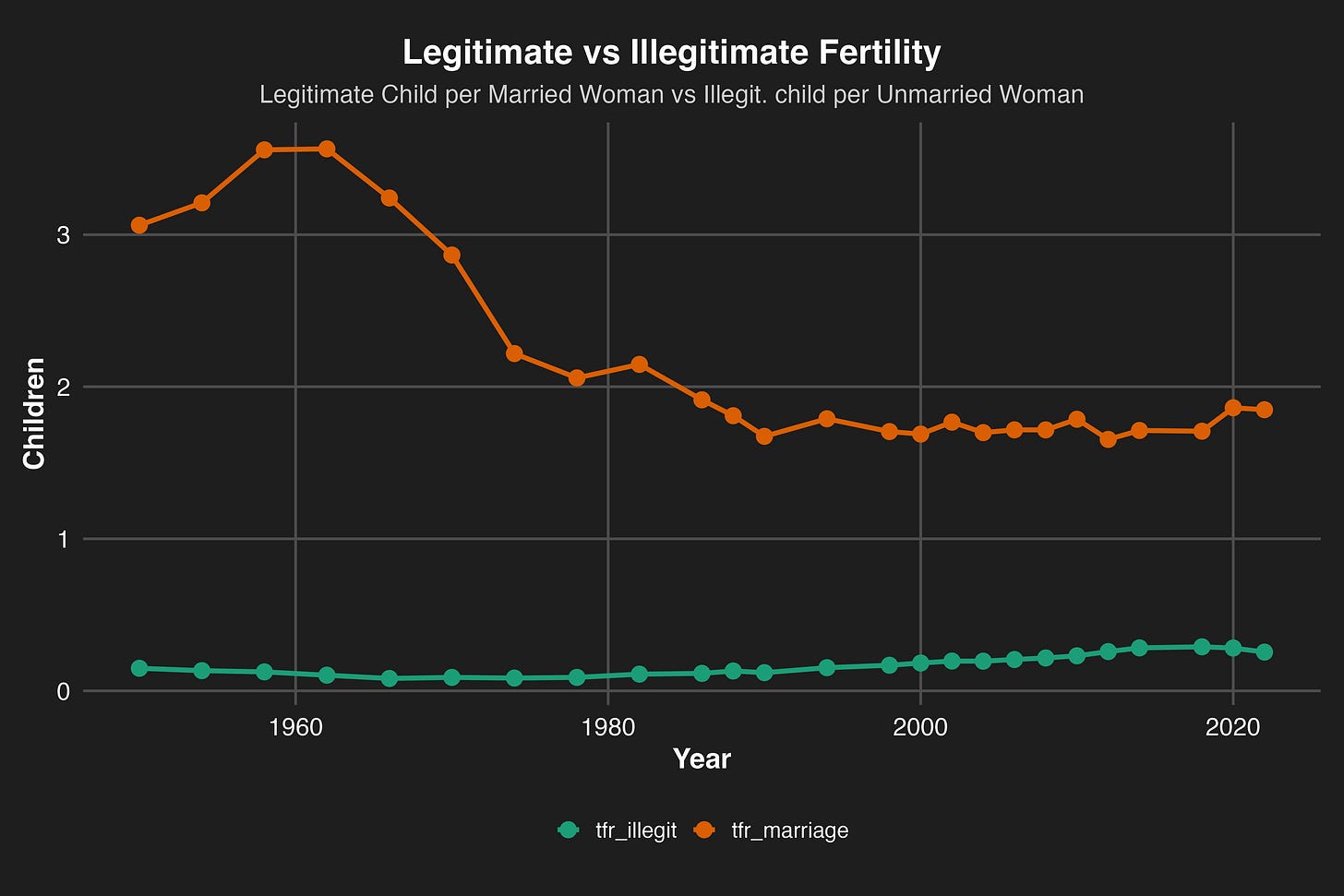

The last chart on marital vs. non-marital fertility was the marital fertility out of all women, so women as a whole produce 1 legitimate child per woman and .5 illegitimate children per woman. But most women are not married. The chart above shows the number of children per married woman vs the number of children per unmarried woman.

Married women almost have a fertility rate of 2. In fact, their rate has been around 1.8 since the 90s, and this is also the number of children Germans desire on average. This suggests that missing marriage is a fundamental mechanism in low TFRs.

It looks like TFR is far under 2 primarily because not everyone marries. Declines since 1990 in TFR are primarily associated with declining marriage rates. But these are in turn primarily due to there being less young people because of a declining population. That means the latent fertility rate is really at equilibrium since 1990, and increases in marriage ages since then haven’t affected the TFR.

Meanwhile, the large within-marriage TFR declines from 1960 to 1980 weren’t associated with changes in marriage timing. They were associated with declines in marriage rates, but it doesn’t look like declining marriage rates caused the within-marriage fertility decline. Rather, the declining rates in marriage probably caused the post-1980 declines in the share of the TFR that is legitimate children.

Conclusion

So what is going on here? It looks like that the most recent decline in fertility happened for an outside reason, within marriage, between 1960 and 1980. At the same time, likely for the same reason, the rate of marriage within young people fell. This caused the proportion of young people to fall later, further dropping the rate of marriage, but not within young people.

The average age of marriage, an age over 30 characterizing the Postmodern Marriage Pattern, seems to mostly lag behind the fertility of marriage. The fertility fell first, and then people began delaying marriage, since now they only planned to have 1.8 kids per marriage, which can usually be done when marrying in your early 30s.

Non-marital fertility has changed a little bit, but not much. The decline in the TFR is mostly declining fertility of married couples. To fix the problem, then, the fertility of married couples needs to be improved. To do this, it’s necessary, but not sufficient, to reduce the average age of marriage, ideally by at least 10 years. After that, it is necessary to induce young couples to aim for more than two children. Ideally this is done by paying the best young couples to reproduce more, creating eugenic fertility-trait correlations while also increasing the TFR. It’s like a stack of books, we have to undo it in reversed order.

See page 41 (51 in the pdf reader) in the link.

Consider this alternative hypothesis:

No-Fault Divorce greatly ncreased the risks with having children in marriage because of the increased likelihood of ending up a single parent.

Every additional child makes single parenthood significantly more difficult.

Therefore, the legalization of No-Fault Divorce caused the marital TFR to drop.

However, few married people would explicitly admit that they're having fewer children because of fear of divorce. So they'll give alternative explanations.

Similar to how executives retire early "to spend more time with their family".

Primary factor is that women are not dependent on men anymore. If this is not fixed, nothing else will work.