Understanding IQ qualitatively

Most people can hardly pass middle school algebra

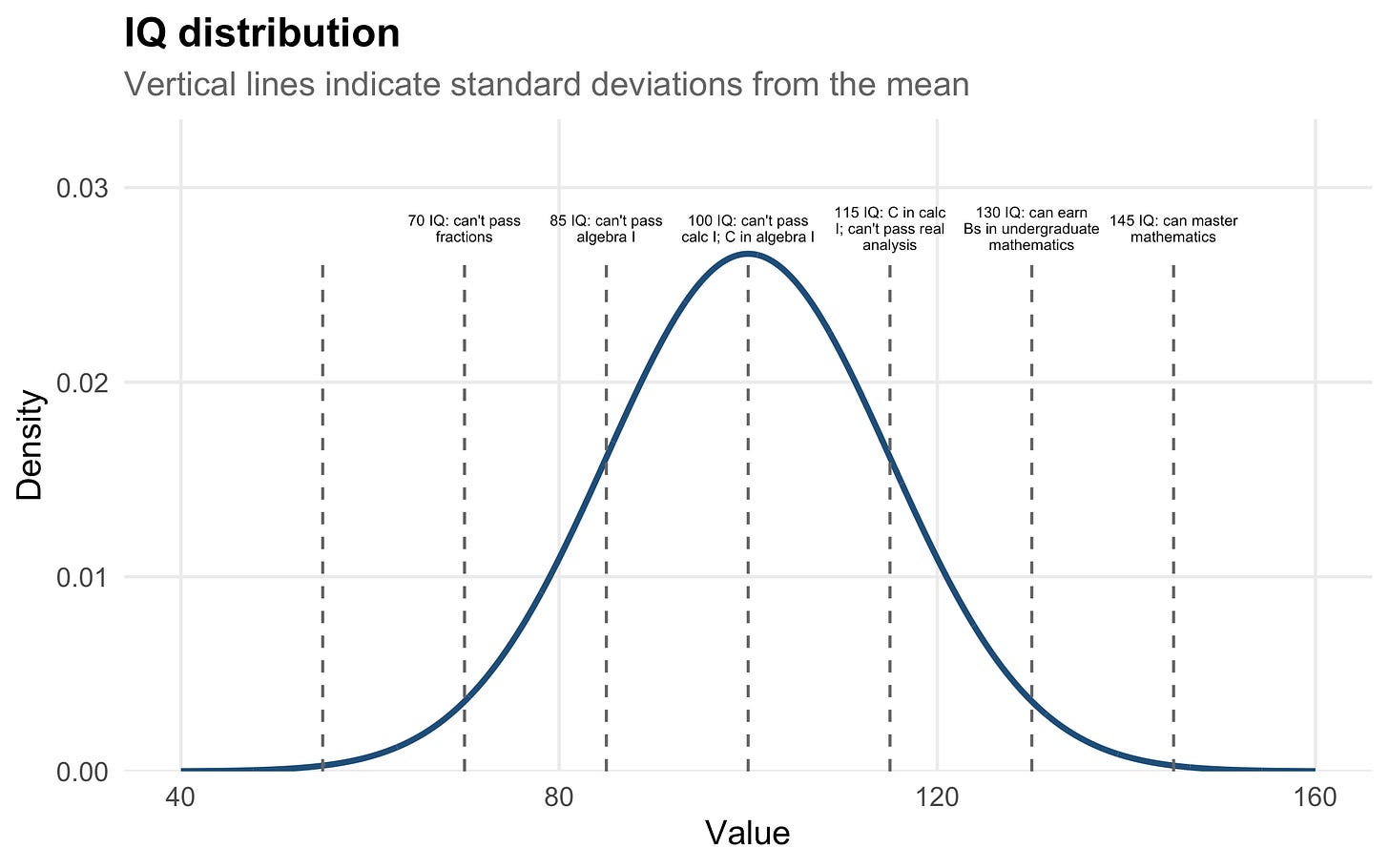

It would be really useful to understand IQ qualitatively, but there is very little research on this. To understand what I mean by this, consider the following hypothesis ensemble:

70: mentally retarded, if wild then savage and incapable of social organization beyond a small clan, can’t pass fractions at school

85: doesn’t believe in stories, tactile. Can’t pass algebra 1

100: can’t pass calc 1, C tier in algebra 1, sees world through feelings, things they can touch only. believes in stories and myths

115: can’t pass real analysis, C tier in calc 1, sees the world through stories. Believes in abstract principles as feelings. Capable of designing rigid protocols for institutions

130: sees the world through data. can get at least C/B average in an undergrad math degree. Capable of considering broad unexpected outcomes of feelings based principles.

145: sees the world through mathematical models which produce data. capable of contributing at the highest level to knowledge. Can design a state with complex laws that always change based on circumstance and can implement a eugenics program because he understands the necessary math.

We can see from this that it would be nice to know what kind of math ability, ethics, and social organization people of different intelligence levels are capable of. As of yet, IQ only means moderate correlation with some life outcomes like SES. Being able to say “people under 120 IQ can’t do a bachelor’s degree in mathematics” or something similar would be a real game changer. I suspect something like this is true; I see a lot of people who just can’t math at all.

We can tentatively check how calibrated these numbers are. In the Chicago Public School system, 21% failed Algebra 1, but the system was 40% black, so it’s plausible the mean IQ of the students is under 100; our model predicts 21% failure if the mean CPS student IQ is 97 with a standard deviation of 15. So we’re pretty close.

As for 100 IQ people being C-tier in Algebra 1, about 40% of students who take Algebra 1 in 8th grade repeat it, even though only about 20% fail it. And ostensibly, people who take it in 8th grade tend to be a little smarter than average, so 40% makes sense given that people under 100 IQ can only get to a thin understanding of Algebra 1.

For calculus, 35% of people who attempt it in high school in the US fail. But only about 20% attempt to take it in high school. So a decent estimate is that 13% can pass calc 1 in high school, which is close to what I put above (15% of people are above 115 IQ). It seems about 25% of people with university diplomas have passed a calculus class, and about 50% of people get a university diploma, so that’s 12.5% of people. In other words, Calculus filters >85% of people.

Only about 4% of people get a 5 on AP calculus in high school, it’s likely if you can’t do this easily you won’t be good enough at high level mathematics. So that’s roughly people of a minimum IQ of 127. Perhaps at 130 IQ one could get a B average pretty easily in an undergraduate math program.

These numbers may make it looks like less people have pre-requisite intelligence to understand certain math topics than they actually do, since they implicitly assume that all success cleavages in math are due to an intelligence threshold. If work ethic, for instance, effects math performance too, there will be failures who could understand it if they worked harder, and there will be successful people who would not understand it if they worked an average amount. However, these numbers can be interpreted as showing what percent of people are smart enough to grasp a topic, holding their other traits fixed. In some sense, being lazy is an extended stupidity, because lazy people will never think hard with what raw brain power they may have, and therefore will never produce anything really intellectually interesting.

It would be interesting to model thresholds. For example, individual math topics could be interpreted in the IRT framework to have latent discrimination and difficulty. In Item Response Theory (IRT), difficulty is the ability level where someone has a 50% chance of answering correctly (midpoint of the curve), showing how hard an item is, while discrimination (the slope) shows how well the item separates high-ability from low-ability individuals. In other words, high discrimination topics are impassable to people under the steep threshold, while low discrimination topics may vary in difficulty (ie, people over some threshold learn it much faster), but are more amenable to repeat attempts (since, for example, a beneath-threshold person might have a 20% chance of “getting it right”, whereas if the discrimination were very high, they would have a .1% chance).

Discrimination aside, integral solving problems probably have a difficulty somewhere around 115 IQ, quadratic equation problems have a difficulty around 100 IQ, abstract theorem proving problems might have a difficulty near 130 IQ. Sadly it would cost a lot of money to run a large scale study comparing IQ test performance to realized math performance. Maybe an epic based billionaire could fund it?

Incredible work mapping IQ thresholds to actual math performance, the IRT framework application here is really smart. I've noticed somethign similar in tutoring undergrads where there seems to be a cognitive wall around real anaylsis that no amount of effort breaks through. The lazy-as-extended-stupidity framing is kinda brutal but tracks with what we see in practice.

There are no thresholds in real life. Or in item response theory terms, no item has infinite discrimination (loading =1).